We will first look at situations when people want to use dual axis charts, then we explain their problems, and afterward we’ll look at four alternatives: Why people use dual axis charts We’re sorry if that makes our user’s life harder, but we agree with the many chart experts who make cases against dual axis charts.

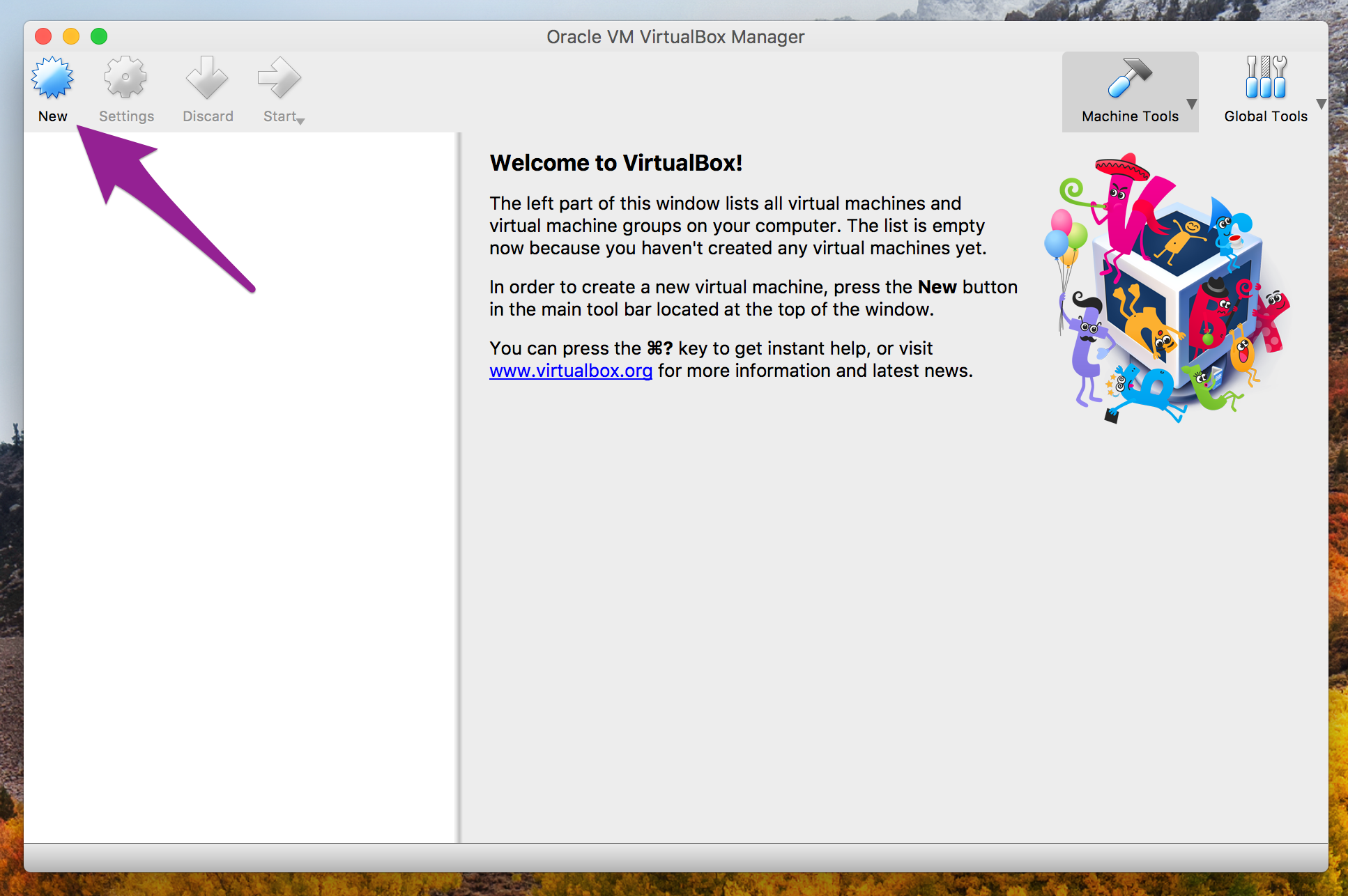

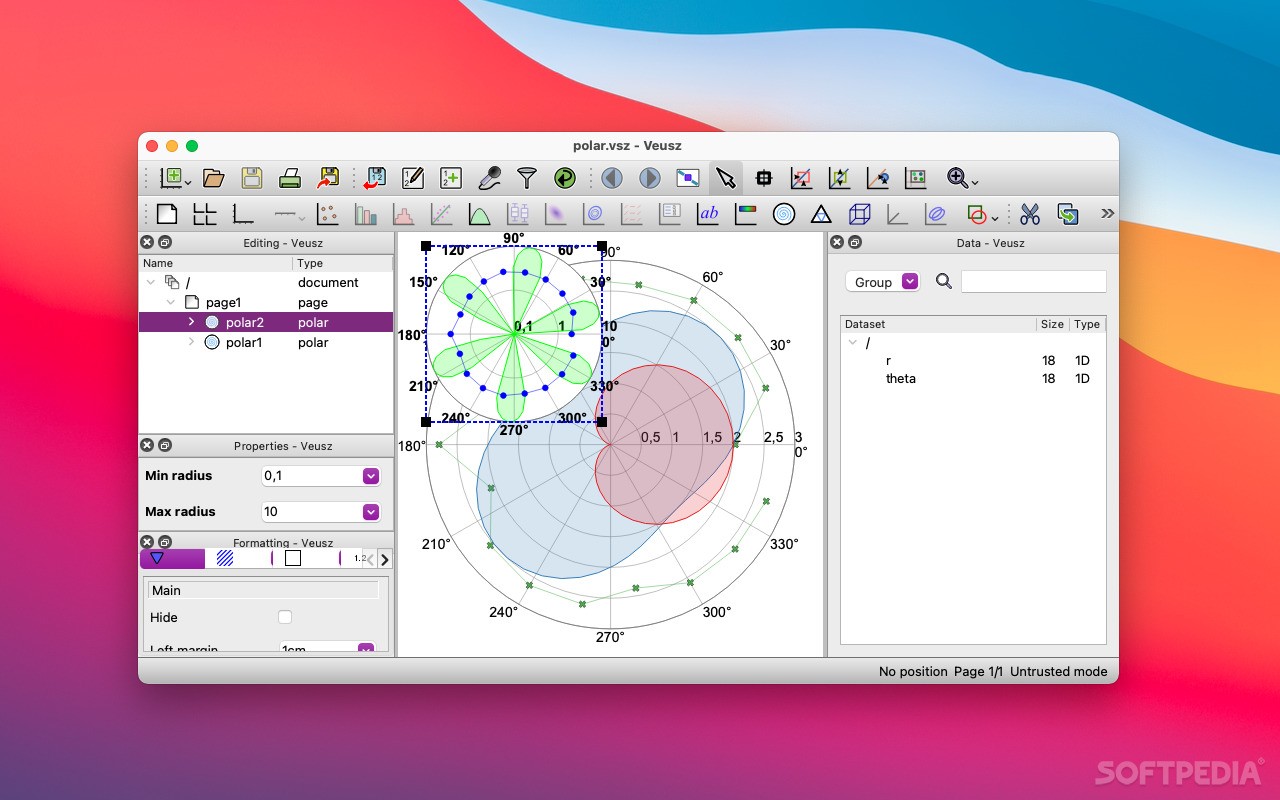

VEUSZ DOWNLOAD MAC SERIES

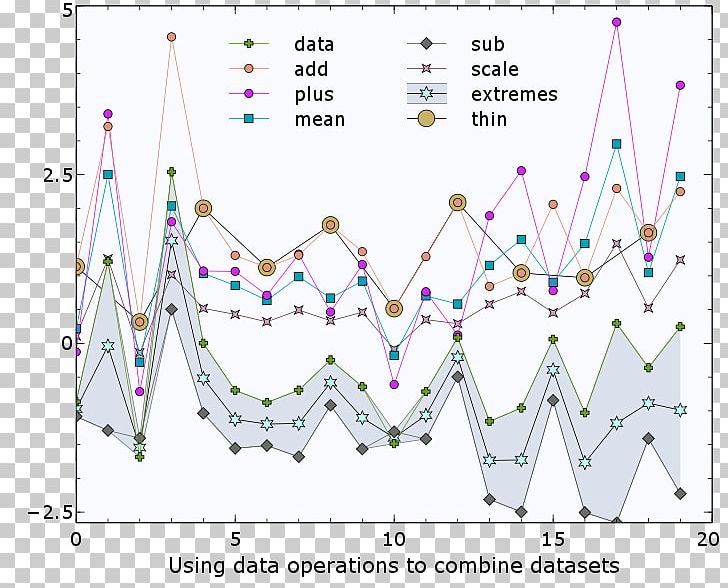

Why do people use dual axis charts? We looked around and found that most people used them to show…ġ …two data series with the same measure, but different magnitudes, e.g. the global GDP on one axis and the GDP of Germany on the other one:Ģ …two data series that show the relative and the absolute values of something, e.g. the GDP per capita on one axis and the absolute GDP on the other one:ģ …two data series for totally different values, e.g. The GDP of a country on one axis and the life expectancy of that country on the other one:Ĥ …one data series, but the y-axis shows different scales, e.g.

The values in Fahrenheit on one axis and in Celsius on the other one:Īs you can see, dual axis charts are often used to show two different data series with a different magnitude (=number range) and/or measure (GDP, life expectancy, etc). Often, their goal is to compare two trends with each other. Giving readers the possibility to do so makes a lot of sense – but there are some reasons why a dual axis chart is not the way to go. Let’s have a look at the problems with dual axis charts before thinking about alternatives: The problems with dual axis charts In fact, of these four use cases, we think that only the last dual axis chart can be used without any doubt, since it only uses the second Y-axis to show an alternative scale and not a second data series. Let’s use some real Worldbank data for the German GDP and the global GDP between 20 to explain that: Here’s the problem in a nutshell: The scales of dual axis charts are arbitrary and can therefore (deliberately) mislead readers about the relationship between the two data series. This chart has two different y-axes: The left axis shows the global GDP with a range from $40 to $80 trillion. The right axis shows the German GDP with a range between $2.5 and $4 trillion. A second axis sounds like a good solution – but there are three problems we have with them: Zero baselines at different heights can mislead The measure (US-Dollar) is the same, but we have a wildly different magnitude. The proportions of the two scales are often different from each other in dual axis charts. If the left axis would go down to zero, the chart would be twice as long. This is how both axes look like when we extend them to zero: If the right axis would go down to zero, the chart would be almost three times as long. So while the chart looks like the German GDP and the global GDP go up at roughly the same rate (at least until 2014), they don’t. The global GDP increased by 80% until 2014 the GDP of Germany by 40%.

Most readers are used to line charts with just one scale. So when they see a line chart with two scales, their intuition goes into the normal “that’s how I read a line chart”-mode: “Oh, two lines, cool, same rate, interesting”.

Readers actively need to remind themselves that these two lines have less of a relationship than they’re used to seeing in a line chart. So how small is the relationship between these two lines? Let’s go crazy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)